Let’s Unfix McKinsey’s Helix Organization

Author: Jurgen Appelo

It’s hard not to become a skeptic in a world where many things around us are fake. We have fake news, fake emails, fake shoes, fake IDs, fake videos ... even fake quotes. Sometimes, things are fake because the fakers make money off of gullible people. Other times, the fakers are just too lazy to truly understand or do the real thing.

Not surprisingly, there is also fake agile.

“Many in the Agile community bemoan the rise of “Agile theatre” – in which enterprises deploy some performative Agile branding without making any fundamental changes to how projects are managed.”

As an example of fake agile (or agile theatre), let’s look at McKinsey’s Helix Organization, a “new” organization design model described in several articles on McKinsey’s blog. The start of these articles is quite promising:

As our business environment has become more complex and interconnected, we seem to be replicating that in our organizations, creating complex matrix structures that don’t work anymore.

Indeed! The matrix model doesn’t work.

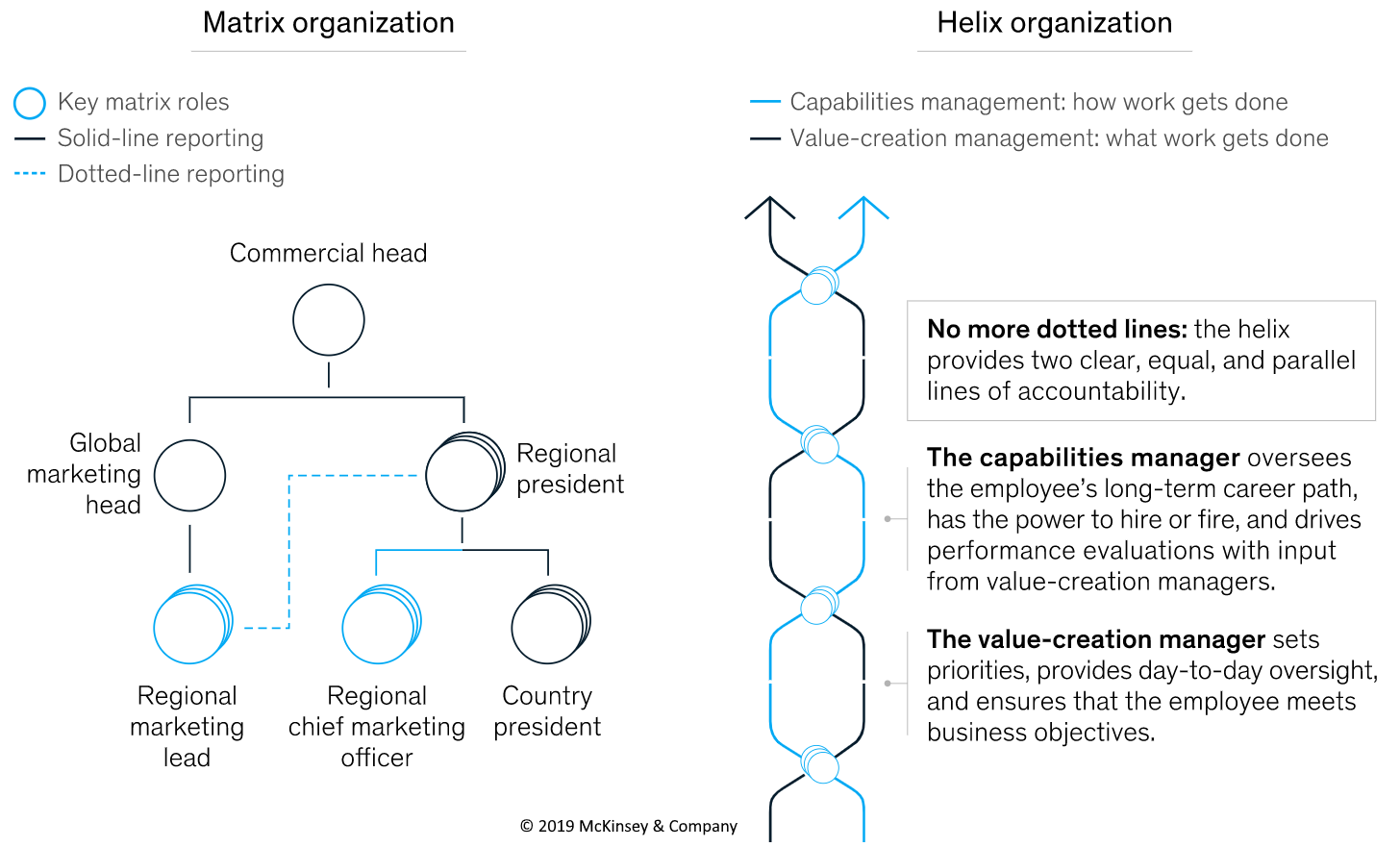

Matrix management is an organizational structure in which individuals report to two (or more) bosses, described as solid line and dotted line reporting. In a matrix structure, an employee has a line or functional manager (the “solid line”) and a project or business unit manager (the “dotted line”).

The problems with matrix structures have been known since 1978. Experts and organization designers found that (among other things) the matrix structure doesn’t work well because organizations end up with too many middle managers and too many escalating conflicts.

“One key finding from organizations with matrix structures is indeed that higher-level managers become overloaded because lower-level managers are unable to resolve conflicts and therefore refer conflicts to the executives. In other words, an unintended consequence of a matrix structure is actually to make the organization more centralized and to remove accountability from lower-level managers.”

The matrix structure makes an organization less agile!

Despite its many problems, McKinsey & Company has tried to make the most of the matrix organization even up to 2018. Fortunately, this has changed. McKinsey has started promoting a new alternative to the matrix organization, called the “helix organization”. The helix is supposed to solve the problems of the matrix. But, does it?

No, not at all.

The matrix is dead. Long live the matrix!

From McKinsey’s articles:

The secret of the helix lies in disaggregating the traditional management hierarchy into two separate, parallel lines of accountability—roughly equal in power and authority, but fundamentally different.

Yes, you read that correctly. The “secret” of the helix organization is splitting traditional management into two managers per person, just like the matrix organization did in the 1950s of the last century.

People leadership tasks typically done by one manager are decoupled into two sets of tasks performed by two different managers. One emphasizes value creation, or what gets done, by setting priorities for the business – overseeing day-to-day work, creating value and helping deliver a full and satisfying customer experience. The other is attuned to capabilities, or how work gets done. They develop people and resources, set standards for working and drive functional excellence.

But, but ... That is the matrix structure as I have known it for decades! One line manager does functional management, and one business manager does project management. That’s the most typical matrix solution. And McKinsey’s helix model, as an “alternative” to the matrix, says ...

One boss [the capability manager] provides and makes decisions about one set of things (such as hiring and firing, promotions, training, and capability building); the other boss [the value-creation manager] makes decisions about another set of things (such as prioritization of goals and work, daily supervision of task execution, and quality assurance).

So, the helix IS a matrix. It is precisely the same thing. People still have a functional boss and a project boss.

McKinsey only changed four letters of the word.

In contrast, in the unFIX model, people have only one manager who is a Chief in a Governance Crew. There is no “capability manager” and no “value-creation” manager.

Coordination is replaced with more coordination

One of the problems of the matrix organization is that too many managers spend too much time coordinating things with each other. The workers “belong” to one manager, and they “work for” another manager, which requires quite a bit of communication. The agile community sees such coordination as waste.

But how does McKinsey see that?

The two managers—one of which we’ll call the “capability leader,” the other the “value-creation leader”—have to agree on a number of things: who and what to deploy to projects, initiatives, and business units, for example, and how much these human and other resources are going to cost.

In the helix structure, managers coordinate with each other because they have to agree on things.

The capability leader would arrange to have a new resource deployed to fill Jaime’s former role, likely with some overlap to properly hand over the role—again, all in consultation with the value-creation leader.

The coordination problems of middle management in the matrix structure are “solved” in the helix structure by having middle managers spend their time consulting, arranging, and deploying resources with each other. Brilliant! Why did nobody come up with such a solution before? (Oh wait, my functional manager and project manager did that in 1998. They called it a matrix structure.)

In contrast, in the unFIX model, people are expected to self-organize and self-allocate across the Crews in a Base. No managers need to be involved in coordination. For an excellent example of this, check out the Pipedrive case study.

The Product Manager becomes a real manager

McKinsey’s helix structure introduces the “value-creation leader” as one of the two bosses. (In the matrix structure, the typical title was project manager or business unit manager.) What would that mean for agile models and frameworks like SAFe, LeSS, and unFIX?

The value-creation leader clarifies objectives, discusses and sets day-to-day priorities, and measures and provides feedback on delivery against her goals and targets.

In a helix organization, those who manage customer value (in other words, the Product Managers and Product Owners) become actual managers of the other team members. They clarify objectives, set day-to-day priorities, and measure people against targets. We would call this a red flag and an anti-pattern in the agile community. But, product managers, be warned! This is not an easy role.

Value managers need to let go of the idea that they can only manage the business when they have a “solid” line to those they manage.

Right. In the helix structure, Product Managers and Product Owners have to get used to the idea that they must share the responsibility of managing resources with the capability managers. Sorry folks, it’s only part ownership of people, not complete ownership.

Life is hard for value creators!

In the unFIX model, Product Managers (or Product Owners) could be on a Facilitation Crew or Experience Crew, helping the Value Stream Crews deliver the best value. Alternatively, they could be Captains of those crews. Either way, they are not anyone’s boss. Life in an unfixed organization is even harder!

The Functional Manager remains a manager

In McKinsey’s helix model, the traditional line manager becomes the “capability leader” who focuses on the functional side of things.

The capability leader is available if Jaime wishes to go to him with a question on, say, marketing best practices, the company’s standards and guardrails with respect to branding, or a new industry standard—or when she feels she needs coaching or advice with respect to the functional subject matter: marketing.

In other words, nothing changes here. The functional manager (who decides on compensation and everything) is still seen as everyone’s coach and supervisor. He is the one people turn to for career advice and better compensation. This patronizing approach of the line manager as the wise mentor and boss is Management 2.0 all over.

But, wait!

Capability managers need to let go of interfering in day to day business decisions.

Indeed. We already tried “letting go” with the matrix model. My line manager and project manager already did their best with exactly this principle in 1998. It didn’t work out so well. I quit my job within a year.

In the unFIX model, the Chiefs of a Base are the only managers. Their main concern is who works in the Base and how do we pay for that. They can delegate everything else. There are no functional managers because Functional Forums can take care of best practices and company standards. And a Facilitation Crew of mentors can take of coaching and career advice. There is nothing to do for a capability manager.

Let’s allocate some resources!

The agile community has a long history of self-organization practices (such as swarming, Open Space Technology, open allocation, and dynamic reteaming). People flock to the teams and product areas where they feel they can learn and contribute the most.

How does McKinsey see that?

It helps those companies that have already achieved agility at the team level make agility a reality across the whole enterprise by making resource allocation more dynamic.

Right. Agreed. The “resource allocation” needs to be dynamic. So, what does McKinsey suggest?

The team and resource fluidity associated with agility goes hand in hand with well-delineated functional “homes” where employees return for training and coaching, with relatively unchanging core processes, and with stable governance arrangements. Indeed, that backbone facilitates the redeployment of people from one business to another and allows for speedier and more flexible staffing of special initiatives that fall outside traditional boundaries.

Wait ... what?! Resource fluidity? Well-delineated? Unchanging core processes? Stable governance arrangements? Redeployment of people?

Whenever shifts of resources are decided on in the resource allocation process, a transparent talent marketplace is required to staff the right people at the right time to the right topic. This requires that leaders have a detailed understanding of available human resources.

McKinsey’s solution for dynamic reteaming is to call people resources, create a resource allocation process, and require that managers—they call them leaders—have a detailed understanding of who can do what and who is needed when and where.

Because the stupid cows cannot figure this all out with each other. Obviously.

In contrast, dynamic reteaming (using any agile practice for swarming and open allocation) was one of the inspirations behind the unFIX model. No resource allocation by managers is needed.

The helix has so many benefits!

McKinsey & Company believes that their helix organization comes with lots of benefits.

The biggest advantage of the helix organization is the flexibility, which people can be shifted between value-creating areas where the organization sees the highest return on its investment. To enable this, best-in-class organizations attach this process to a quarterly priority setting process (e.g. as we see it in many agile organizations a quarterly business review “QBR”).

That’s right. The best-in-class agile organizations reprioritize their business objectives, and reallocate their resources, once per quarter! (Never mind that Tesla does this every three hours.)

And the resources feel very empowered.

Jaime is so empowered in this model that instead of saying she has “two bosses,” she tells colleagues that she doesn’t have a boss at all.

And the helix structure is super flexible because everyone has two bosses.

This model creates a lot of flexibility, as the people ownership in the capability axis enables flexible shifts of people into the value creation axis.

And the resources LOVE terminology such as “people ownership” and “shifting people into a capability axis”.

The model also requires a stronger culture of collaboration, to align resources and business requirements in the best way, a culture of trust and partnership.

And bosses aligning their resources creates a culture of tremendous trust and partnership.

🤦🏻♂️

In other words, nothing really changes

Maybe I’m being a bit too cynical. It could be that there’s something in the helix model that’s not like the matrix structure we already had.

These managers are neither “primary” nor “secondary,” as is the case in the matrix.

In McKinsey’s model, both bosses are equally important. There is no solid line or dotted line. The managers have different but equal powers, they say.

In a helix structure, it’s vital that the two people leaders are aligned and willing to participate in employees’ performance reviews. Processes that underly evaluations, and hiring and firing, should incorporate feedback from both the capability and value-creation leaders (even if the former is ultimately responsible for aggregating the feedback and delivering the review).

Ah, it appears not. The capability leader (functional manager) is ultimately responsible, and so they are still an itsy bitsy teenie weenie more important than the value-creating leader (project manager). A solid line and a dotted line, after all.

Nothing has changed.

If it quacks like a matrix, then it’s a matrix

It’s good to see that McKinsey has acknowledged the matrix structure has its problems.

Many companies become frustrated by matrix design structures. CEOs often complain that their organizations are overly complex, slow down decision making, make it difficult to get things done, and sow disillusionment among middle managers.

And I’m happy that McKinsey has tried to come up with an alternative.

The secret to this model’s success lies in disaggregating the traditional split of management tasks into two, distinct parallel lines of accountability that are roughly equal in power and authority, but fundamentally different.

Sadly, McKinsey’s new helix model is fundamentally different in absolutely nothing. Their helix model is, in fact, precisely the same as the matrix we already had.

It is important to note that this is not a new idea, but so far unnamed.

Indeed, the helix model is not a new idea. But it already had a name. We called it a matrix.

It will come as no surprise to some readers that McKinsey has reinvented something that already exists by simply renaming a problematic concept. After all, they’ve done it before.

“Take McKinsey’s promotion of an “agile transformation office.” An unnecessary rebrand of an existing concept, the program management office, that goes against the fundamental principles behind agile. Every point McKinsey lists as a difference to a PMO is an almost exact description of a PMO.”

Every point McKinsey lists as a difference to a matrix is an almost exact description of a matrix.

And that’s fake agile. Or, as some people call it, agile theatre.

“Just as organisations can use green-washing to appear more sustainable, so they can use Agile theatre to appear to be more agile without making any fundamental changes.”

We can and should do better.